The ThirdEye project supports farmers in Mozambique and Kenya with their decision making in farm and crop management by setting up a network of flying sensors operators. Our innovation is a major transformation in farmers’ decision making regarding the application of limited resources such as water, seeds, fertilizer and labor. Instead of relying on common-sense management, farmers are now able to take decisions based on facts, resulting in an increase in water productivity. In Mozambique, we currently have 6 active local operators providing service to more than 3,500 farmers over more than 1,600 ha. Since last year, the ThirdEye service is also implemented in Kenya.

Background

A key factor in enabling an increase and efficiency in food production is providing farmers with relevant information. Such information is needed as farmers have limited resources (seed, water, fertilizer, pesticides, human power) and are always in doubt in which location and when they should supply these resources. Interesting is that especially smallholders, with their limited resources, are in need of this kind of information. Spatial information from flying sensors (drones) can be used for this. Flying sensors offer also the opportunity to obtain information outside the visible range and can therefore detect information hidden for the human eye (Third Eye). Nowadays, low-cost sensors in the infra-red spectrum can detect crop stress about two weeks before the human eye can see this.

The ThirdEye project supports farmers in Mozambique and Kenya by setting up a network of flying sensors operators. These operators are equipped with flying sensors and tools to analyse the obtained imagery. Our innovation is a major transformation in farmers’ decision making regarding the application of limited resources such as water, seeds, fertilizer and labor. Instead of relying on common-sense management, farmers are now able to take decisions based on facts, resulting in an increase in water productivity. The flying sensor information helps farmers to see when and where they should apply their limited resources. We are convinced that this innovation is a real game-changing comparable with the introduction of mobile phones that empowered farmers with instantaneous information regarding markets and market prices. With information from flying sensors they can also manage their inputs to maximize yields, and simultaneously reduce unnecessary waste of resources. In summary, the missing information on markets has been solved by the mobile phone introduction, the flying sensors close the missing link to agronomic information on where to do what and when.

Flying sensors

Thanks to our innovation, farmers’ demand for key agricultural information will be satisfied by means of an extension service based on flying sensor (drone) information. The deployment of flying sensors is unique in its ability to provide farmers with real-time, high-resolution, and on-demand information. We provide essential agricultural information:

- At an ultra-high spatial resolution (NDVI)

- With unprecedented flexibility in location and timing

- Based on wavelengths not observable by the human eye

- With a country-specific business oriented approach.

To this end, we use low-cost high-resolution flying sensors (drones) in a development context to ensure that farmers will get information at their specific level of understanding, and simultaneously develop a network of service providers in Mozambique and Kenya.

A flying sensor is a combination of a flying platform and camera. Reliable flying sensors are on the market in a wide-range of categories each with its specific characteristics. Based on the consortium’s experiences over the last years low-cost flying sensors have been identified that are excellent equipped for our innovation. Typically, a flying sensor flies at a height of 100 meter and overlapping images are taken about every 5 seconds. This results in individual images covering about 50 x 50 meter and an overlap of 5 images for each point on earth. So, in order to cover 100 ha 500 images are taken during a flight.

The use of Flying Sensor is unique and no comparative techniques exist that provide farmers with real-time high-resolution information. The use of satellites to provide farmers with spatial information has been promoted but has three main limitations: they have fixed overpass times, the spatial resolution is low, and the presence of clouds halters the information. It is unlikely that, within the coming decades, progress in satellites will be real competitors of flying sensors. Another category of comparable techniques to provide farmers with information is the use of ground sensors. Typical examples of these sensors are soil moisture devices, soil sampling and laboratory analysis, crop sampling and laboratory analysis. However, all those sensor techniques have the common limitation that information is only local point representative, while the main question farmers have is regarding to spatial differences. Moreover, these ground sensors are in all cases too expensive to be used by small-scale farmers.

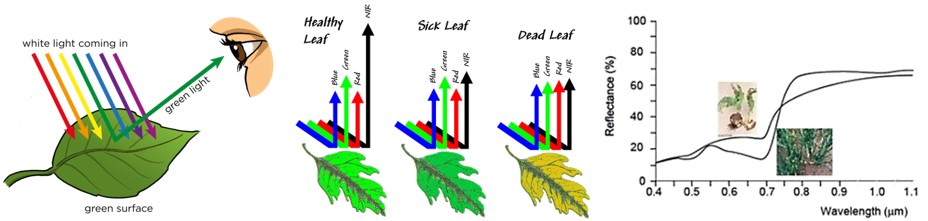

Our flying sensors have cameras which can measure the reflection of near-infrared light, as well as visible red light. These two parameters are combined with a formula, giving the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI). This information is delivered at a resolution of 2×2 cm in the infra-red spectrum. Infra-red is not visible to the human eye, but provides information on the status of the crop about two weeks earlier than what can be seen by the red-green-blue spectrum that is visible to the human eye. NDVI is the most important ratio vegetation index and says something about the photosynthesis activity of the vegetation. Moreover, NDVI is an indicator for the amount of leaf mass, and therefore, ultimately biomass. In general, open fields have a NDVI value of around 0.2 and healthy vegetation of around 0.8. NDVI values give an indication of crop stress. This can be caused by a lack of water, lack of fertilizer, pests or abundancy of weeds.

NDVI technology

When light falls on a leaf, reflection occurs. The amount of reflection of green light (0.54 µm) is very high, making plants green to the human eye. Healthy vegetation does not reflect much red light (0.7 µm), since it is absorbed by chlorophyll abundant in leaves. In the near-infrared spectrum (0,8 µm) the amount of reflection increases rapidly to 80% of the incoming light. This increase is caused by the transition of air between cell kernels. This is characteristic for healthy vegetation.

Damaged plant material does not show this increase in reflected near-infrared light. Moreover, the reflection of red light is much higher than in healthy plant material. By measuring the reflection in these spectra, damaged plant material can be distinguished from healthy plant material (Schans et al., 2011).

Progress

From 2014 to 2017, FutureWater has been granted support from the Securing Water for Food program, funded by USAID, Sida and the Dutch Government of Foreign Affairs, for piloting the use of flying sensors to support farmers in Mozambique with their decision making in farm and crop management. In Mozambique, we have transferred our technical skills to local ThirdEye operators over the past 3 years. We currently have 6 active local operators providing service to more than 3,500 farmers over more than 1,600 ha. These operators are able to support over 400 small-scale farmers, by collecting information and sharing it with farmers on weekly basis. Based on the information, farmers take decisions on where to do what in terms of irrigation, fertilizer application and pesticides, helping them improve their water productivity. Furthermore, they now have the capacity to deal with technical issues and are very skilled in providing advice to farmers. As a result, the farmer’s water productivity was increased by 55%, meaning less water is used to achieve the same crop yield as without ThirdEye services. ThirdEye has evolved since 2014 from a start-up to becoming the leading company in Mozambique in the field of mapping and monitoring services for farmers based on aerial images, which will continue to expand its activities over the coming years.

Since last year, the ThirdEye service is also implemented in Kenya as part of the Smart Water for Agriculture program implemented by SNV. Last month the first round of training was given to 5 operators, who will be serving at least 2,000 smallholder farmers the coming months. Training consists of flying sensor use, technical skills, safety and protocols, imagery processing and consultancy. After this, the operators will start working regularly in the regions of Meru and Nakuru. Here they will go the farmer’s fields, conduct flying sensors flights, process the images and give advice on improving their agricultural practices. Next to the service for smallholder farmers, ThirdEye delivers various services to medium and big sized farmers.

Links

- Project website

- Project video

- Follow us on Twitter

- Flyer of the project

- Project description (in English)

- Project description (in Portugese)

Publicaciones relacionadas

2019 - FutureWater Report 190

ThirdEye Kenya – Water Productivity Report

Van Opstal, J.D., M. de Klerk

2019 - FutureWater Report 192

ThirdEye Kenya: Flying Sensors to Support Farmers’ Decision Making – Final Report

De Klerk, M., J. van Til, F.K. Julius

2018 - FutureWater Report

ThirdEye Kenya: Flying Sensors to Support Farmers’ Decision Making – Summary of year 1 results

De Klerk, M., J. van Til

2018 - FutureWater Report

ThirdEye Kenya: Flying Sensors to Support Farmers’ Decision Making – Interim Report

De Klerk, M., J. van Til

2018 - FutureWater Report

ThirdEye Kenya: Flying Sensors to Support Farmers’ Decision Making – Inception Report

De Klerk, M., J. van Til

2017 - FutureWater Report 169

Monitoring Water Productivity: Demonstration Case for ThirdEye Mozambique

Droogers, P., G.W.H. Simons, N.I. den Besten, J. van Til, M. de Klerk

2017 - FutureWater Report 170

A First-Order Water Productivity Assessment for the APROVALE Project, Mozambique

Simons, G.W.H., N.I. den Besten, P. Droogers

2017 - FutureWater Report 166

Change in Water Productivity as a Result of ThirdEye Services in Mozambique

De Klerk, M., P. Droogers, G.W.H. Simons, J. van Til

2016 - Thesis Report

Identifying and designing business models for innovative Flying Sensor services in Mozambique

J. van den Akker